Written by Melanie Carden

Build empathy. Create beauty. These are the noble goals of the humble-hearted director of Slave Cry and TRI, Jai Jamison. Jai has shadowed directors Omar Madha on AMC’s TURN, and Tucker Gates on Showtime’s Homeland. He served as the Showrunner’s Assistant to Reggie Rock Bythewood on the Apple+ Series, Swagger.

Now in Los Angeles, where he’s a writer on the CW show Superman and Lois, Jamison’s roots are in Richmond, Virginia. The city’s arts community and complex identity have influenced his work much the same way golfing with his father has—Jamison’s work is peppered with his life experience. As a storyteller, Jamison is a master weaver, pulling threads from his own background and blending them with the subject matter—a seamless tapestry of shared human experience.

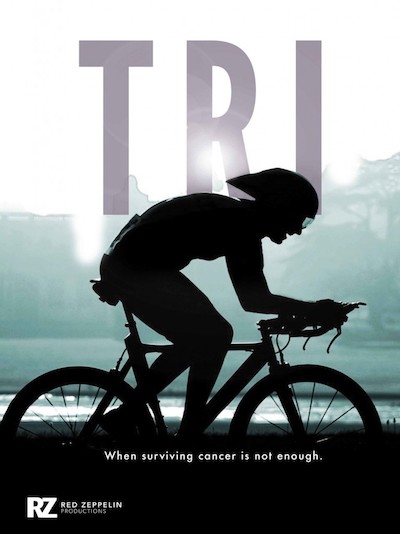

Jai’s award-winning feature TRI is an action sports dramedy about triathlons, which led to his selection for the 2016 Shoot Magazine New Director’s Showcase. Every triathlete has a powerful story–a deep well of fortitude from which they draw for training and endurance–both emotionally and physically. Natalie, the lead character, is notorious for leaving things unfinished. The story follows her triathlon journey–from its inception as a far-fetched idea, to crossing the finish line as her legs repeatedly give out from underneath her. The first US-based feature-length movie about the competitive sport of triathlon, TRI is a cinematic viewfinder of vignettes that capture the very human capacity to use emotion as a catalyst for transformation.

Jai’s award-winning feature TRI is an action sports dramedy about triathlons, which led to his selection for the 2016 Shoot Magazine New Director’s Showcase. Every triathlete has a powerful story–a deep well of fortitude from which they draw for training and endurance–both emotionally and physically. Natalie, the lead character, is notorious for leaving things unfinished. The story follows her triathlon journey–from its inception as a far-fetched idea, to crossing the finish line as her legs repeatedly give out from underneath her. The first US-based feature-length movie about the competitive sport of triathlon, TRI is a cinematic viewfinder of vignettes that capture the very human capacity to use emotion as a catalyst for transformation.

The most critical stories to tell, he shares, are those that “open us to each other’s experiences in a way that feels relatable.” It must tie us together and “excavate our humanity.” The director’s work, in this regard, is steeped in emotion across a broad cross-section of human struggle—from the dark chokehold of racism to the psychological and physical endurance of triathletes.

Slave Cry—a short filmed in Richmond—pairs Jamison’s writing and directing with his sister Courtney in the lead role of McKinley Harris. Slave Cry was The Commonwealth Award Winner at the 2019 Virginia Film Festival and was recently accepted into the 2021 Pan African Film Festival. Harris is a young, black actress navigating the exhaustive audition circuit. A graduate of Juilliard, Harris’s fortitude has been withered by the endless string of auditions for historical slave-related roles. In fact, most of her auditions call upon her ability to bypass her moral conflicts and reach into the depths of her lineage—to conjure the septic, all-consuming pain that slaves endured day-after-day. McKinley is forced to “slave cry,” as she calls it, for these auditions—an ugly cry that—if done well—involves tears, face contortions, snot, and a voice drenched in a life of terror. She is called upon to do this over and over—one audition after another.

The opening scene of Slave Cry is understandably uncomfortable to watch—a close-up of the actress performing her slave cry for a panel of white casting agents. Seeing how emotionally draining it was for his sister, Jai decided to shoot the scene as efficiently as possible to reduce the emotional toll. He explains that when a film’s content is emotional, the actors’ needs must come first. That might be in the form of “conversations, a closed set, advance notice of a tough scene in the schedule, or additional time to prepare.” Jai’s empathy and understanding in the creation of the story are paramount to its ability to resonate with—and build empathy within—the audience.

I watched Slave Cry’s protagonist, Harris, move through her day—onto her pay-the-bills job as a Civil War Era-clad tour guide at the Robert E. Lee monument. Visitors casually wearing their newly-purchased confederate flag tchotchkes—some with the flags tucked under their arm so they can take photos of the statue that celebrates a commander’s life in the Confederate Army. These men were a militia of citizens that violently enacted its ideology. their beliefs were described by Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens when he proclaimed, “that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.” Harris recounts for the monument’s visitors that Lee’s army was the “most famous of the Confederate armies.”

She says this with a smile because that’s her job. She says this with a smile that I can only imagine it takes Herculean strength to force across her face.

Actress Courtney Jamison in Slave Cry.

She ends her tour guide spiel, and the camera pans down to her feet— in red Converse Chucks—as she steps off her lectern of sorts—a dismal grey box that could easily double as a soapbox or pulpit. As Jai intended, it’s reminiscent of the auction blocks that a slave of that era would have stood on. As Harris steps down, she merrily announces, “Next, we’ll be visiting a slave market.”

Harris’s forced smile and determination mirror the actress’s day-to-day life in Richmond. It echoes the daily life of many Black people. Richmond offers a complex socio-emotional landscape for telling Black stories— highly concentrated historical layers of fertile land for the director’s “excavation of humanity.” Jai speaks of Richmond almost as a beloved character. He describes it as an artistic community and a “confluence of people, balancing and reckoning the past and deciding their future.” And also, “a little radical.” Harris’s red Converse Chucks—inspired from another project of Jai’s—represents that community, working toward a sustainable balance of past, present, and future—historic, artsy, and a little edgy.

As Richmond and other cities large and small across the nation reckon the past, there have been emotionally-charged debates. Monuments, educational namesakes, and other celebrations of racism speckle the landscape like fiery-hot red pepper flakes caught in the throat. It is a constant chokehold on the Black and non-White communities. “It says to future generations ‘these are important people; this was an achievement,’” Jai laments. But with a nod to Zora Neale Hurston, he insists it’s not enough to open a wound with a story’s words and imagery; you have to provide healing—a salve. In Slave Cry, the director juxtaposes the Lee monument with that of Maggie Walker to soothe the caustic burn in the throat.

In July 2017, the city of Richmond unveiled its Maggie L. Walker monument. Ms. Walker—Black and eventually paralyzed and aided by wheelchair—was the first Black businesswoman to charter a bank and serve as its president (1903), among other civic accomplishments. The 10-foot bronze statue stands in her likeness, complete with her checkbook in-hand—an enduring symbol of Black excellence but also a poignant reminder of the much remaining work ahead to eradicate systemic racism.

Inequality and restricted access—from generational wealth to simply feeling safe—remains an incalculable hurdle for many Black people and communities. To be a Black American is to rail against bias—conscious and unconscious—with every waking breath. Yet, despite the constant barriers, the Black community does not lack strength and influence. In the eyes of Jai Jamison, one such leader is his father, Calvin Jamison, Sr. Mr. Jamison, a businessman and avid golfer, is celebrated in Slave Cry’s hilariously poignant golf scene.

A nod to his father, and an homage to the barbershop scene in Coming to America, Jai shot the scene at the city driving range. Here, in contrast to most golf locations, Jai comments that even when growing up “there was a decent number of Black folks.” Though his father had long been a golfer, it was an especially memorable time as Tiger Woods began his epic ascent in the traditionally White sport of golf. The scene is a riff on the lively barbershop debate so ironically portrayed in Eddie Murphy’s Coming to America. Slave Cry’s golf scene finds the protagonist’s grandfather, and family friends sitting around at the driving range—hitting balls, sipping beer, and debating about how to pronounce the word “gif.” Like most barbershop debates, there’s both an ease and sharp wit with which it all unfolds. Jamison’s writing of the scene captures the erudite, professional men of his upbringing—his father and father’s friends. The men exchange theories and personal jabs.

“You chunky peanut butter eatin’ motherfucker.”

“You Oxford comma usin’ son-of-a-bitch.”

They lovingly hurl these verbal firecrackers at one another while workin’ on their game. This dialogue is humorous, but the latter comment is also a nod to the highly educated role models in the director’s life. It’s positioned against McKinley Harris’s entrance—fresh off her shift as the “happy-to-serve” Confederate tour guide. When the men ask how auditions are going, she explains it’s a lot of slave crying but that she’ll “get a sassy best friend [audition] here and there.”

In this scene and throughout Slave Cry, Jamison captures the past, present, and future while personifying the Black experience. He tips his cap to those who’ve inspired him—all while building empathy and creating beauty through his writing and directing. His past work can be found on his website. And in the meantime, he’s thrilled to be a writer for CW’s Superman and Lois. His debut episode (episode #7) is slated to air in April of this year.